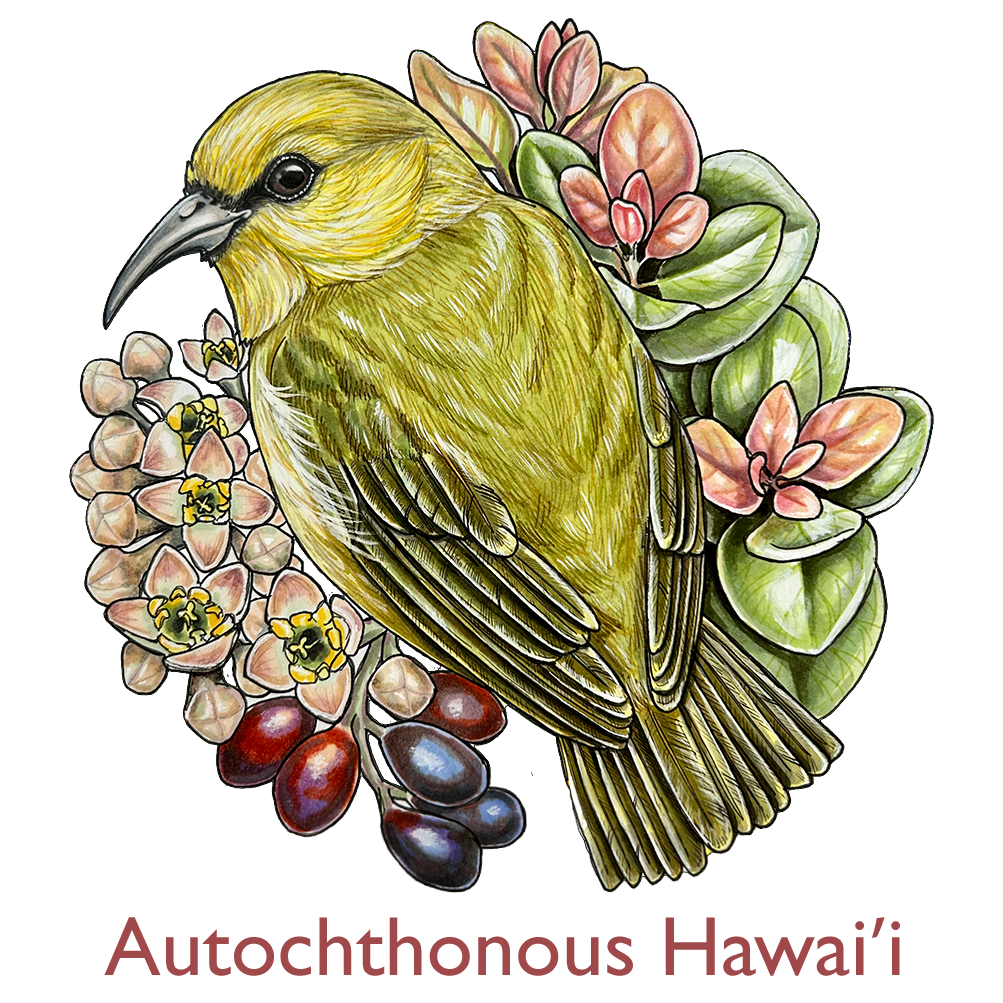

Autochthonous Hawai'i

'I'iwi and hāhā original

'I'iwi and hāhā original

Couldn't load pickup availability

Original 5”x7" illustration.

'I'iwi (Drepanis coccinea) and haha (Cyanea grimesiana ssp. grimesiana).

Hawaiian honeycreepers as a whole are extremely susceptible to avian malaria. These birds evolved over 5-7 million years without malaria or mosquitoes (the vector for this disease). Although ‘apapane and ‘amakihi show some resilience, other honeycreepers are not so lucky; there is a ~90% mortality rate for an ‘i’iwi bitten by a single malaria-carrying mosquito. Mosquitoes are all over, how are there still ‘i’iwi in Hawai'i?

Both the organism that causes avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) and the mosquito that transmits it (mostly Culex quinquefasciatus) are generally unable to proliferate at higher elevations due to cooler temperatures. So, birds like ‘i’iwi are restricted in range to higher elevation forests, occupying a small fraction of their former distribution. O'ahu no longer has high-elevation forests safe from malaria, but other islands do. The problem with this is that climate change is (not so slowly) pushing that temperature gradient up into the last refugia for these birds. 'I’iwi, ‘ākohekohe, kiwikiu, ‘akikiki, ‘akeke’e are some of the honeycreepers that are most at risk for this introduced disease. Some of these birds have as little as 2-3 years projected before their ultimate demise—unless we take immediate action.

Although things are dire for these manu, the last of a 7-million-year legacy, they are not hopeless—one of the most promising tools we have to curb the spread of malaria (and thus the death of these birds) is the incompatible insect technique, or Wolbachia. Despite misinformation, Wolbachia is not a GMO, it is not untested, and it is not dangerous to people. Wolbachia is a naturally-occurring bacteria found in insects worldwide!

C. grimesiana grimesiana is not strictly an O’ahu Cyanea, they historically occurred on Moloka’i as well, but have not been recorded there in some time. This plant is one of about 79 Cyanea species—all of which are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. This genus is considered autochthonous, in that it originated in its present location (Hawai’i). The Hawaiian Campanulaceae (bellflower family) are an evolutionary wonder, with SIX endemic genera arising from a single colonization event! Within Cyanea, approximately 90% of species are single-island endemics. C. grimesiana is an exception, found on both O’ahu and Moloka’i, however it has not been observed on Moloka’i for some time. Cyanea are notable for being one of few endemic Hawaiian plants that have defenses, and fewer still that these defenses appear to have evolved in situ rather than being a trait carried over from their ancestral colonizing lineage.

Hawaiian honeycreepers and Hawaiian lobelioids co-evolved. Over millions of years, they slowly adapted in unison, with the lobelioid flowers elongating to tubes perfectly suited for the bills of the honeycreepers, whose bills elongated and decurved to suit the flowers. As you can imagine, such a tight evolutionary connection has a downside when both groups are in significant decline. Without honeycreepers in sufficient numbers to pollinate them and disperse their seeds, Cyanea and their cousins declined. In addition, cattle, pigs, goats, alien slugs, and other pests have been devastating to these truly unique plants, as well as outcompetition with invasive plants.

I hope one day we can see ‘i’iwi again on O’ahu, and Cyanea thriving in more than just a few protected areas.