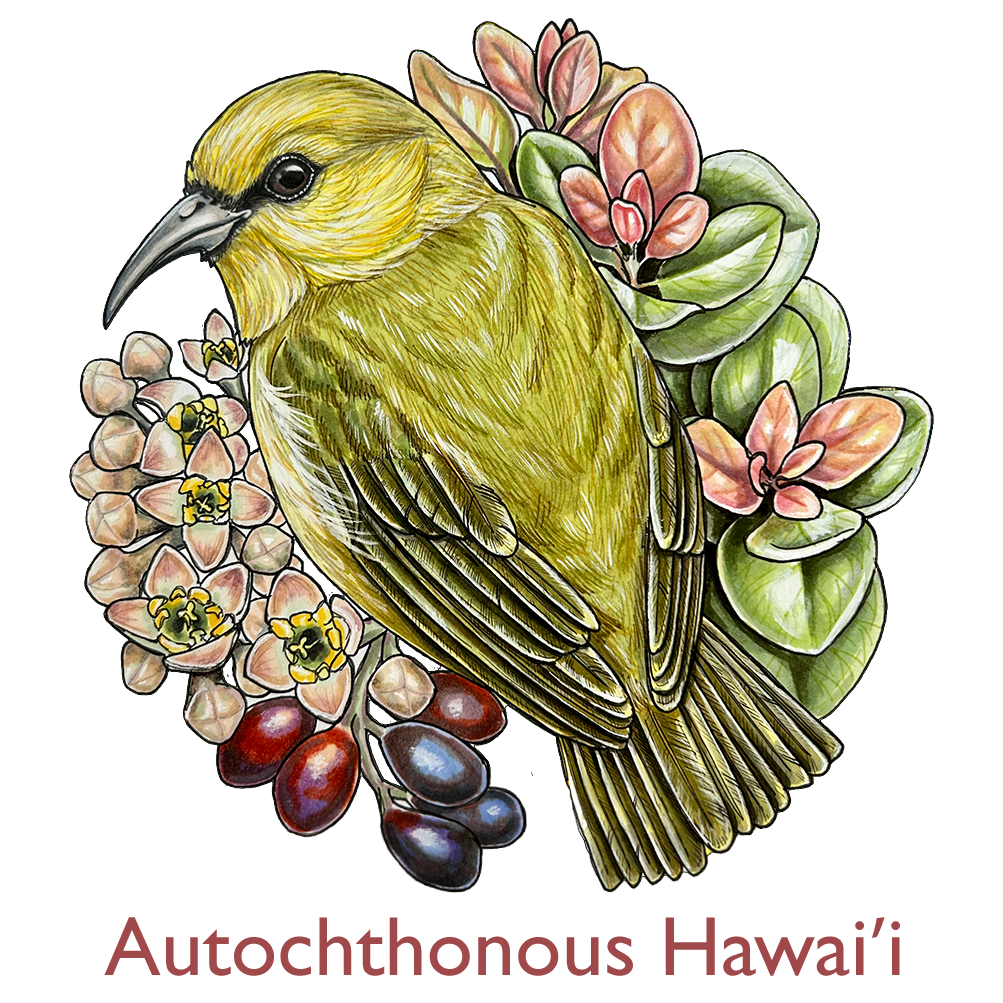

Autochthonous Hawai'i

Short tailed albatross original

Short tailed albatross original

Couldn't load pickup availability

Original 5.5"x7.25" illustration.

Short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria albatrus).

There’s something magic about short-tailed albatrosses. With their distinct candy bills and golden glow, their gigantic size compared to other North pacific albatrosses, and their quiet, stoic nature, they really are a marvel to behold.

STALs were once very common. Now classified as vulnerable by the IUCN and endangered at the federal and state level, STALs were hunted extensively for the feather trade during the 1900s. Millions of birds were killed. By the time the Japanese government declared a ban on albatross hunting, there were few left, and by 1949 were assumed to be extinct. Thankfully, like other albatrosses, juveniles don’t return to their nesting site for years after hatching, so while the adults had been killed, there were still some youths out at sea, who eventually returned to Torishima island (their main nesting colony). The world population is now estimated to be around 4,400 birds—a tiny fraction of their former population.

STALs have a small breeding range. Aside from Torishima and a select few other islands in Japan, there is one breeding pair of STAL on Midway atoll (George and Geraldine), plus the non-breeding Kure pair mentioned previously. Social attraction has been utilized to encourage expansion of breeding range, which involves placing decoy STALs in selected sites. Efforts for expanding their breeding range is crucial—the majority of the world population breed on Torishima, which is an active volcano, and eruptions and landslides are very real threats to this colony.

Despite their common name, their tails are no shorter than others in the genus Phoebastria, to which our other Hawaiian albatrosses belong. This genus is considered sister to Diomedea (the great albatrosses), and diverged some 12-15mya.

There are two of these beauties who nest on Kure, affectionately referred to as our “golden girls”. This pair, although bonded for many years now, are non-breeding… both of them are female! They each lay one egg in their nest bowl, which they create in the same spot seasonally. They take turns brooding, each spending several weeks at a time incubating their infertile eggs. This one is the “older girl”—identifiable by having a golden nape rather than the chocolatey nape that younger birds have (although, the “younger girl” has gotten quite gold too, making them hard to tell apart!). I’ve been lucky enough to see Lonesome George on Midway, plus several other lost shorties that found their way on Kure (all of them younger birds). STALs have a very special place in my heart, and I hope their numbers can continue to grow.

The primary threats to STALs are the fishing industry and volcanic eruptions; other threats include introduced predators, climate change and sea level rise, and plastic pollution. Heavy metal contamination and POPs (persistent organic pollutants) also factor in.